It’s almost impossible to get through cancer treatment without some kind of impact on your emotional wellbeing. For some people, their emotions are front and centre during treatment. For others these may not until weeks, months, or even years after treatment. Some young people also find themselves feeling quite isolated in their experiences, as cancer isn’t often something they have in common with many people in their lives. This can make it harder to talk about, seek help, or know where to begin in managing how you feel.

In time, everyone gets to a point where they feel ok about their cancer experience- sometimes on their own, and sometimes with the support of professionals. It’s important, though, to feel like you have ways of managing emotional challenges as they come up along the way. The information here is all about tools for dealing with difficult thoughts and feelings, understanding why they happen in the first place, and life hacks for good emotional health overall.

COMMON FEELINGS AND CONCERNS

Though everyone experiences life after treatment differently, there are some common things that young people describe feeling:

-

These symptoms might indicate depression, although many of them overlap with how you might feel when building yourself back up after chemo. If you’re not sure, or if you’ve been experiencing many of the following for two weeks or more, talk to your GP:

- Feeling irritable, sad or stressed

- Feeling angrier than usual

- Dwelling on thoughts of failure or how others are treating you

- Feeling guilty, worthless or hopeless

- Lots of negative thoughts – expecting everything to go badly for you or in the world around you

- Less interest in the things you usually enjoy

- It’s a huge effort to get through the day, or you just can’t manage to face certain things

- Sleeping differently – too much or too little

- Feeling tired all the time, even if you’re getting enough sleep

- Problems concentrating or paying attention to things

- Loss or appetite or over eating

- Thinking you’d rather not be around, people would be better off without you, or that life isn’t worth living

- Distancing yourself from others or avoiding people altogether

-

The symptoms below might indicate anxiety that goes beyond everyday feelings. There are many different kinds of anxiety, and having some anxious feelings is a normal experience for everyone. So think about whether your symptoms seem to be more intense than you would expect for the situation, if they don’t seem to be about anything in particular, or if they don’t really seem to go away. If you’re not sure, have a chat to your GP.

- Feeling overwhelmed or frightened

- Feeling nervous or a sense of dread a lot of the time

- Tension or feelings of being on edge all the time

- Panic, or fearing that you might panic

- Lots of thoughts about bad things happening

- Worrying a lot about everyday things, and not feeling able to stop the worry

- ‘Overanalysing’ things

- A ‘busy mind’

- Avoiding people, places or activities that you’re worried about

- Physical symptoms, such as: increased heart rate, shaking, butterflies in your stomach, tight chest, breathing fast or shallow, sweating, nausea or vomiting, dizziness, trouble sleeping, problems with concentration

-

Most people who have been successfully treated for cancer will experience some thoughts about it coming back. This is incredibly normal, and often reduces the further away from treatment you get.

Your treating team have probably talked to you about the chances of cancer returning for you, but that doesn’t mean you won’t still worry. Some worry is normal- after all, you’ve had cancer once, so you know now that it can happen to you. The good news is that there are ways to help you manage these feelings. If you recognise yourself in the symptoms below, or your fears are significantly impacting your enjoyment of life, then have a chat to your GP about speaking to a psychologist for specific support.

- Seeing your GP or specialists a lot more for tests or reassurance

- Noticing and worrying about almost any physical change

- Avoiding scans or other follow up recommendations

- Feeling too scared to make or commit to plans for the future

- Being generally unsure what the future holds

- Stress, anxiety, worry, and fear

- Physical signs of stress, such as muscle tension or more frequent illness

- Difficulty eating and sleeping

- Problems with your memory or concentration, finding yourself easily distracted

- Not participating in or enjoying activities in the same way

-

Going through cancer is a life-changing- and sometimes life-threatening- experience. Some people might experience the below symptoms of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) after cancer. All of these symptoms are part of the normal way our brains help us make sense of a traumatic event. However, if you’ve been experiencing a lot of them for a month or more, have a chat with your GP.

- Intrusive memories, flashbacks or dreams about parts of your cancer experience

- Feeling scared or upset thinking about cancer or your own experience

- Difficulty remembering parts of your experience

- Avoiding reminders of your cancer experience

- Thinking negatively about yourself or others

- Lots of negative emotions such as anger, guilt or shame

- Having trouble feeling positive emotions

- Feeling distant or cut off from others

- Trouble falling asleep or waking up often

- Problems concentrating

- Feeling like you need to be aware or prepared for danger

- Behaving in ways that might be considered reckless or destructive

-

Body image is a way of describing how you feel about your body- how it looks, functions and feels. It’s normal to feel some anxiety, anger or distress about the changes to your body from your cancer treatment. It’s also normal for it to take some time to get used to these changes, and how you now feel about them. Remember that no matter what has happened to your body, you are still you. But if you’re noticing any of these feelings are affecting how you live your life, it may be time to share them with a professional who can help you make sense of it all. If this is the case for you, start by talking to your GP.

- Loss of confidence

- Shame, anger, anxiety or sadness

- Feeling weak, vulnerable, or unsure what your body can still do

- Not feeling as masculine or feminine as before

- Disconnection from, or hatred of your body

- Not able to look at scars or changed parts of your body

- Worry that you won’t be attractive to your current or any future partners

- Changes to your sex life and intimacy

- Self-consciousness and hiding parts of your body

- Feeling anxious about meeting new people

- Wanting to go out less, or avoiding leaving home

- Grief for what you’ve lost- health, vitality, strength, attractiveness, or physical parts of your body

- Worry that life won’t go back to normal

- Loss of confidence

- Anger, either towards yourself or others

- Feeling worthless or damaged in some way

- Feelings of emptiness, or not feeling anything much at all

- Feeling lost, like you don’t quite know where you’re heading

- Not feeling like yourself, or trying hard NOT to be the person you were while you were sick

- Frustration with how long it’s taking you to feel better, or with other people expecting you to go back to ‘normal’

- Feeling left behind in life

- Grief for what you’ve lost- time, experiences, or expectations for your future

Many people feel down, worried, overwhelmed or lost at different times in their lives. This is particularly normal for teens and young adults, as you’re often going through more changes and transitions during this stage of life than you will at any other. So while everyone is different in how they feel about their cancer experience, don’t worry if things don’t feel exactly right.

SO WHAT’S GOING ON?

One of the first ways to start to manage your emotional experiences is to understand them. Basically, they are our brain and body doing their best to help us through a difficult situation. This is best explained by our threat-response system, which is also sometimes referred to as ‘fight-flight-freeze.’

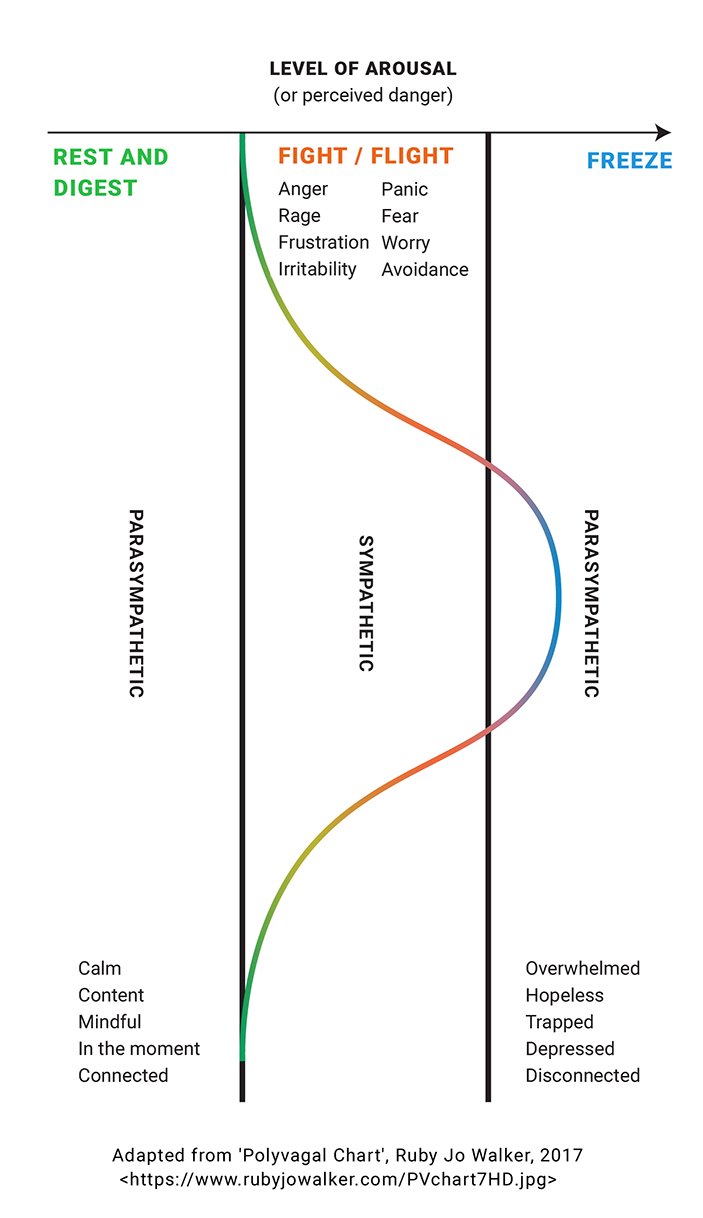

Our bodies have two main systems that manage how we assess danger, and how we engage with the world around us. These are the sympathetic nervous system, and the parasympathetic nervous system. These systems respond to the presence or absence of threat in our environment, and how alert we are to that threat.

At low levels of threat or arousal, we are at our most content, and engaged with the world in a positive way. This is our parasympathetic nervous system at its best. But as our sense of perceived danger increases, our sympathetic nervous system kicks in, throwing us into fight or flight. This is a very active response- either we’re moving towards the threat in fight, or running away in flight.

But if our level of danger or arousal becomes too intense, then we get the opposite end of parasympathetic nervous system. Things start to shut down, we disengage from the world, and any kind of action becomes a challenge. This is the freeze response.

For a graphic showing how this works and the kinds of feelings associated with each, tap the image below.

One problem with our fight-flight-freeze system is that it’s designed to deal with an immediate threat, one that can be eliminated quite quickly. So it was really useful when we were cave dwellers on the lookout for sabre-toothed tigers. We could stab it with a spear, climb a tree, or play dead- threat gone! But the problems you might be facing after your cancer experience can’t be immediately resolved in the way our threat-response system deals best with danger. You can’t run away from feeling like you don’t know yourself anymore, or punch your fear that cancer might come back. You can’t play dead when someone mentions cancer on social media, or run so fast that you catch up with your Year 12 formal, starting your first job or going to uni with your mates.

HOW YOUR BRAIN CAN MESS WITH YOUR EMOTIONS

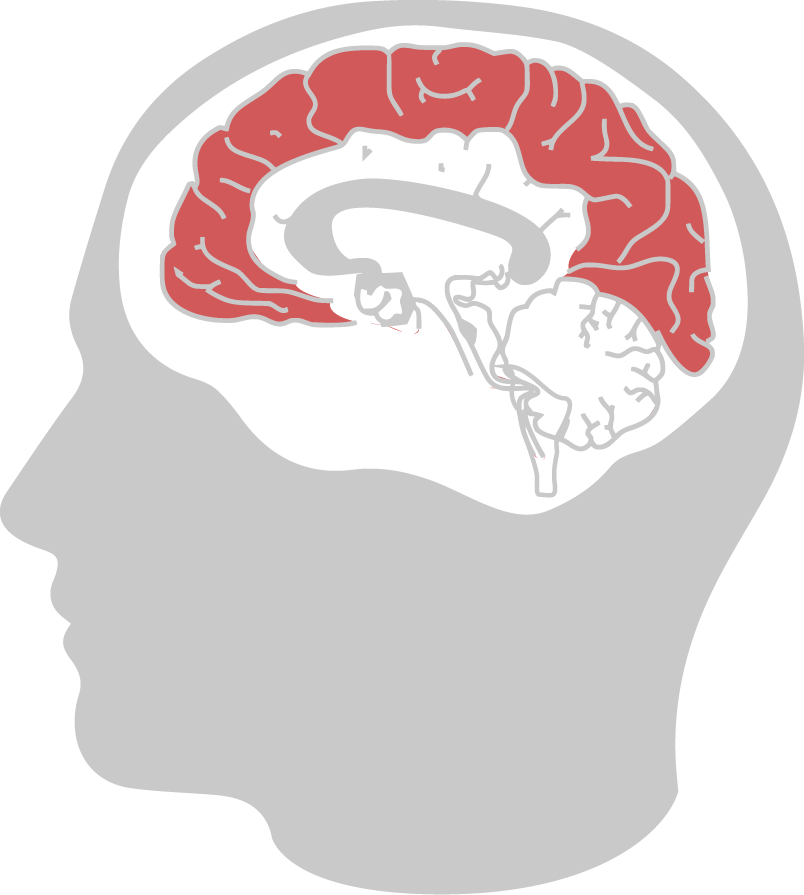

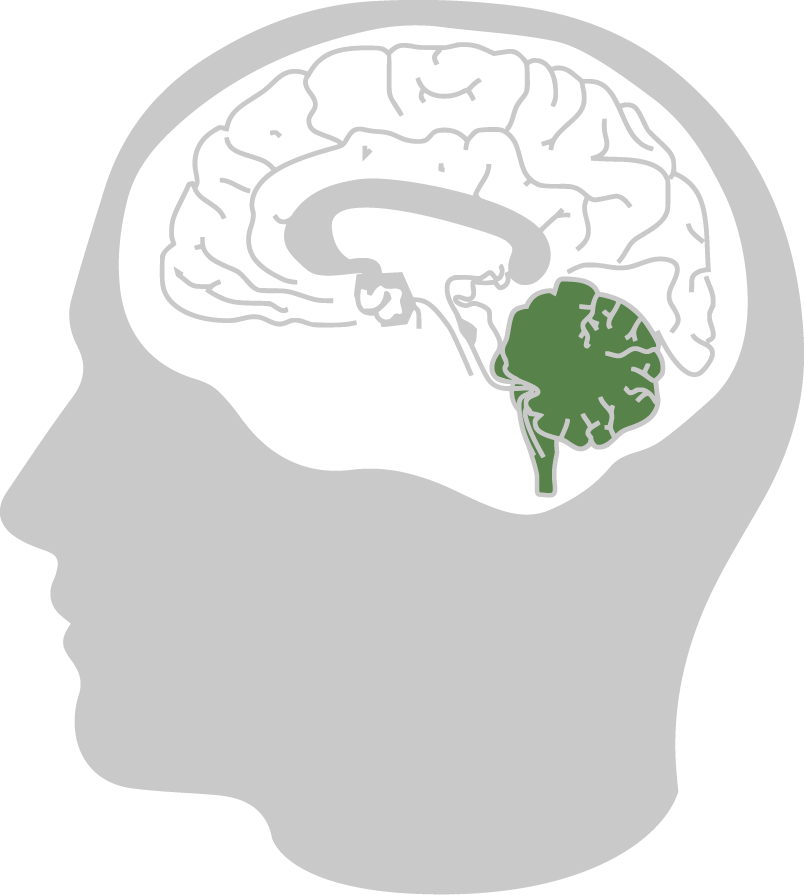

To understand this we need to look at how our brain is structured in three separate but integrated parts, which together manage what we need to be a functioning human.

CORTEX (INC. PRE-FRONTAL CORTEX)

- Most recently evolved part of our brains

- Enables conscious thought, the ability to think about, interpret and create our own understanding of the world around us (including ourselves and other people)

- Can sometimes override our immediate threat response and some bodily functions (e.g. breathing rate)

- Is bypassed in extreme threat or intense emotional reactions (but helps us make sense of these experiences later)

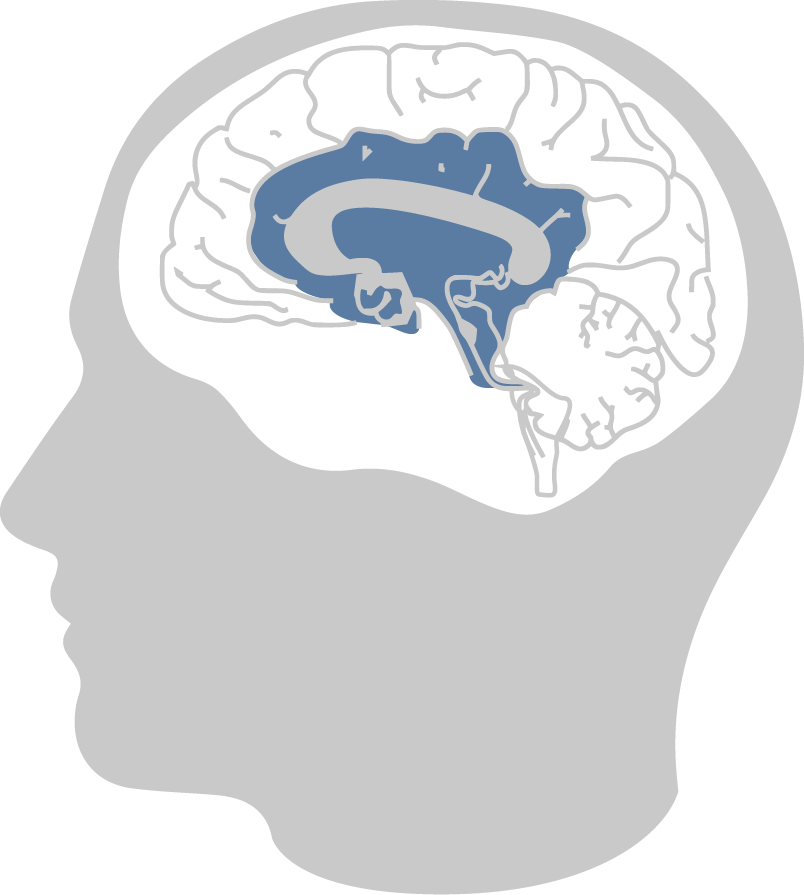

SUBCORTICAL (INC. LIMBIC SYSTEM)

- Responsible for emotions, connection to others and relationships

- Provides information (through our feelings) of whether things in our environment are good or bad

- Amygdala prompts an immediate survival response when faced with a threatening situation

- We can experience and respond to these emotions without conscious awareness

BRAIN STEM (AND CEREBELLUM)

- Oldest part of the brain

- Message relay centre between the brain and body to regulate basic physical processes (e.g. heart rate, breathing, organ function, energy levels, sleep and wakefulness)

- Triggers fight-flight-freeze response, and makes the decision about which option we use when under threat

- No conscious awareness of our own or others’ thoughts or feelings

(Adapted from the US National Institute for the Clinical Application of Behavioral Medicine, 2017.)

How our brains manage threat hasn’t evolved much since the early humans, but just think how much society has changed in that time. As a result, we don’t always have an effective system for dealing with modern day threats. Cancer and its ongoing consequences are just the kind of danger that our brains aren’t naturally equipped to manage, so they might respond in ways that aren’t that helpful. Often, this means that the different parts of your brain start to work independently, like different members of a sporting team all doing their own thing, and not listening to the calm, strategic leadership of the captain (the cortex). When the brainstem and limbic system start to go a bit rogue on the field, this might feel like a rush of overwhelming feelings, and impulsive or unhelpful behaviours.

By using the strategies below, you’ll be helping your brain get back to working as a unified team. This is how we function best.

HOW TO DEAL WITH DIFFICULT FEELINGS

1. NAME WHAT YOU’RE FEELING

Using words to describe what you’re feeling helps link the different parts of your brain. Language sits in your cortex, and in naming the emotions that start in your limbic system, you’re helping these two parts of the brain connect. This reduces the intensity of the feelings and gives you more options to understand and respond to them.

How you do this depends on what works best for you. You might find it easiest to say the words out loud to yourself or someone else, or to write them down in a journal. You could also quickly jot them down on a scrap of paper or keep a note in your phone.

If you struggle to find words to describe how you’re feeling, there are plenty of examples you can look to to build up your emotional vocabulary (try a feelings wheel).

2. THE POWER BREATH

This is a simple and fast-acting strategy for helping your body shift from its threat-response system to its place of safety: the ‘rest and digest’ state of the parasympathetic system (see graphic above). You can then use your whole brain to think more clearly and make choices about how you might respond to a given situation.

The Power Breath is an alternative to calm breathing that is helpful to use in

times of increased distress or anxiety. It’s simple- the key is to do it once, and do it slowly.

- Breathe in through your nose for the count of four

- Breathe out through your mouth for the count of eight

3. REGULAR MINDFULNESS PRACTICE

Mindfulness is the practice of purposefully paying attention to the present moment. This might mean paying attention to your surroundings, your breath, your body, or any other focus point available right here and now.

This skill helps you to focus on the present, and let distressing feelings be without becoming too attached to them. Like all skills, it is one best improved with practice. Many young people find it useful to start practicing mindfulness with the help of an app such as Smiling Mind.

4. ACCEPTING YOUR FEELINGS

This means making space for the difficult feelings that may come up for you after treatment. Whilst you can’t control your feelings, you can choose how you respond to them. Accepting difficult emotions means letting them be as they are, regardless of whether they are pleasant or painful. Feelings are a part of being human.

Try approaching your feelings as though you are a ‘curious scientist’, trying to understand what they might be telling you. This can be hard at first, but it doesn’t matter too much what you come up with. The process of considering the information your feelings are providing can be just as helpful as the answer you come up with.

FEELINGS ARE JUST LIKE THE WEATHER

You can’t choose or control your feelings, any more than you can choose or control the weather conditions. Life after cancer can feel like being dropped into an unpredictable climate that you’ve never experienced.

Accepting distressing feelings is similar to having an important event planned, when you really want perfect weather. You can hope for the conditions you want, but in the end all you can do is choose how you respond to the weather you get. The best way to deal with the weather is to pack your rain coat and focus on why it is you’re there.

With feelings, let them be there, notice them, and let go of the emotional attachment you give them.

HOW TO DEAL WITH DIFFICULT THOUGHTS

1. CREATE DISTANCE FROM YOUR THOUGHTS (DEFUSION)

A lot of the time it’s easy to get really caught up in your thoughts. This is called ‘fusion’, as in being fused with your thoughts.

It’s easy to treat your thoughts as facts, when actually they are quite literally synapses firing in your brain. Considered that way, they’re not that scary at all. These are the same synapses that are firing as you read these words and convert the squiggles on the screen into a meaningful idea.

You the person have a choice in how you respond to the thoughts of your mind. In fact, this is a key strategy in managing difficult thoughts: you are you, and your mind sometimes behaves in a way that isn’t very helpful to you. In practicing ‘defusion’, you create distance from your thoughts to reduce the power they have. This allows you to notice your thoughts, rather than get caught up in them.

HOW TO IDENTIFY FUSION

If you start to pay attention, you might have a lot of rules for how you think, feel and act. Do you notice that your thoughts contain a lot of ‘should’, ‘have to’, ‘can’t’, ‘always’ or ‘never’? These might indicate that you have a lot of rules for yourself, and these kinds of rules are often unhelpful – especially if they are not very flexible. Some examples of this might be “I have to always be healthy, so I don’t increase my risk of cancer coming back,” or “I got another chance; I should be doing more with my life.”

You might also notice that you make a lot of judgments of yourself and others. For example, do you think you coped well or badly with your cancer? Now that you’ve finished treatment, do you think that you are doing a good enough job of returning to ‘normal’ life? These are all judgments.

Next time you notice your mind getting stuck on particular thoughts (especially if these feel distressing or unhelpful), try the following defusion exercise.

“I’M HAVING THE THOUGHT THAT...”

- Identify a negative thought that often comes up for you, and make it into a short sentence. For example, ‘I’m weak’ or ‘I’m stupid’.

- Fuse with this thought for 10 seconds- get caught up in it, give it your full attention and believe it as much as you possibly can.

- Now, replay the thought with this phrase in front of it: ‘I’m having the thought that...’ For example, ‘I’m having the thought that I’m weak’.

- Now replay it one more time, but this time add this phrase ‘I notice I’m having the thought that ...’ For example, ‘I notice I’m having the thought that I’m weak’.

Hopefully you found that with greater distance from your thought, the intensity of it reduced, and you felt less attached to its meaning. This is a helpful way to deal with any upsetting thoughts that don’t seem to be serving you in any meaningful way.

2. WORRY SCHEDULING

A lot of the time our minds get caught up with particular worries, and just can’t let them go. This can really get in the way of getting on with other, often more important things. And yet, the more we try to stop the worries, the stronger they are.

Here is a quick example of how this works: DON’T think about a camel in roller skates.

How did you go?

One way to help with this is to set a time to worry. Try to make this the same time every day- not close to bedtime if you can help it- and set aside 10 minutes to worry. Really worry, like you’ve never worried before. But once that 10 minutes is up, try hard to let go of all the worrying thoughts that arise. Of course they’ll still come up. When they do, you can thank your brain for raising them (again!), but remind it that you now have a scheduled time to attend to them.

THE ROAD TO EMOTIONAL HEALTH AND WELLBEING

A great thing about the above strategies is that they will also help you to manage all kinds of difficult experiences as you go through life.

Let’s face it, life will continue to present you with challenges, whether these are to do with cancer or not. Although no one feels positive about life all the time, it is possible to foster resilience and create a life that has meaning.

FINDING MEANING

Cancer has happened to you, and nothing will change that. When we struggle with negative experiences, it makes it harder to make space for them in our lives. Maybe you’ve spent time trying to pretend that cancer didn’t happen. Or you might feel like it’s such a constant part of your life that you’ll never move away from it.

Finding personal meaning in the experience helps you to move through it. This doesn’t mean that you have to have loved, or even liked it. But you may notice some aspects of yourself where you feel you’ve experienced growth: personal qualities, attitudes or behaviours that are different, and in some ways better than before. Some examples of this might be deeper relationships with friends and family; not wasting time pleasing others or pursuing things you’re not passionate about; discovering greater spirituality; an increased sense of gratitude; or greater awareness of your personal strengths.

COMMON VALUES

Consider the following list of common values, or areas of life people often consider important. These might help you start thinking about ways there can be meaning in your experience. It’s ok if you can’t- this can be tricky, or it might be too soon for you to feel this way about your experience of cancer.

Wordle created with https://wordart.com/

MAKE A GRATITUDE JAR

Gratitude is the act and experience of appreciating the good things in your life. Practicing gratitude can help to increase happiness and satisfaction with life, and both create and deepen your relationships.

Create a jar or box that is dedicated to your gratitude. Decorate it if you like to make it feel special. Each day, write at least one thing you are grateful for on a piece of paper, and place it in the jar.

You might find this difficult at first, but it doesn’t matter how small or seemingly insignificant it is. You may have really enjoyed your first sip of coffee, or the feel of hot water on your skin in the shower. Or you may be grateful for the people in your life. But keep at it, and watch the jar fill up. You might even like to go through the jar from time to time if you’re having a difficult moment.

LIFE HACKS FOR GOOD EMOTIONAL HEALTH

There are some simple ways that we can all lay the foundations for good emotional health. Try to build all of the behaviours below into your life as routinely as you clean your teeth, and keep coming back to them if you find yourself having a tough time- this is when they’re most important.

- Make a priority, every night

- (with some treats thrown in!)

- doing whatever you enjoy

- Do things every day that are important to you and make you feel good

- Reach out to people who you appreciate and feel good around, and maybe think about reducing your time with any you don’t

- Practice self-compassion- speak to yourself kindly, the way you would like to speak to others

- Give mindfulness a try, and see if you can make it a habit

- Seek help from others, even if you don’t think things are ‘bad enough’ to warrant it

WHEN TO GET HELP

If you find these strategies aren’t making the lasting change you hoped, or if the feelings you’re experiencing are affecting your work, study, relationships, or ability to function day to day, then it’s probably time to reach out for professional support.

A can help you understand more about what you’re feeling and why, as well as tailor strategies to suit you and your specific circumstances.

WHERE TO GET HELP

Generally, the best first step is to speak with your GP. will help you to consider options for next steps, like speaking to a psychologist, social worker or other

One option for accessing mental health services may be through the Better Access scheme. For those eligible, Medicare will rebate up to 10 sessions with a mental health professional per calendar year. This may mean sessions are low cost or free. Most young people seeking support after cancer are eligible, but discuss this with your GP. They will then write up a Mental Health Treatment Plan with you, which is required to get the Medicare rebate.

You can also access mental health services outside of the Better Access scheme, though costs may be higher. Either way, your GP can help point you in the right direction.

FINDING A MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONAL

You can choose your own or be guided by recommendations. You might get some ideas about who to see from:

- Your GP

- Your oncologist or other people in your treating team

- Your personal network- sometimes people are happy to recommend a professional they found helpful, if you and they are both comfortable seeing the same person. All health professionals are bound by confidentiality, so they can’t share information about you.

- Find a Psychologist. This is a searchable database of psychologists from the Australian Psychological Society (although not all psychologists are listed).

- Google it. Many psychologists and social workers have websites, so you might start by googling psychologists and social workers in your local area, or who work with cancer- or health-related issues.

Remember that it’s really important to feel comfortable with the person you speak to. Don’t be afraid to make some phone calls to ask questions and get an idea about their fit with you. In making a decision about the right fit, consider:

- Would you prefer to see a mental health professional familiar with cancer?

- Is there a particular age or gender you feel you relate better to?

- What kind of therapy do they use, and what does that therapy involve?

- What are the session fees, and is there an out of pocket cost after the Medicare rebate?

- What hours are they available, and how often would they like you to attend?

DON'T GIVE UP

USEFUL LINKS AND RESOURCES

There is a huge amount of information available about cancer, mental health and emotional wellbeing. But with so much out there, sometimes you don’t quite know what you’re getting with a quick internet search. It’s important to seek information from websites or organisations that are trustworthy and knowledgeable about cancer and mental health.

Even though it’s often helpful and reassuring to hear about other people’s personal experiences, these aren’t always relevant to your situation, or informed by strong evidence. So, by all means use these personal sources, but always make sure what you find is balanced with well-researched information from your GP or treating team, or from cancer and mental health organisations like the following:

- Australian and international cancer organisations, such as: Cancer Council (Aus), Macmillan Cancer Support (UK), or Livestrong (US)

- Your local youth cancer service – each Australian state has a team of health care professionals specialising in the cancer treatment and care of young people aged 15-25 that you can contact for help and advice (some have a psychologist on staff)

- Youth Beyond Blue – information and support for young people about dealing with low mood/depression, anxiety and other concerns

- Centre for Clinical Interventions – practical factsheets and workbooks about a range of mental health concerns that you can work through on your own

- Being ok… being you (Victorian AYA Cancer Service) – a resource for young people with a cancer experience who identify as LGBTIQ+